The wireless antennas use light to detect minute electrical signals in liquid environments, showing promise for biosensing in medical diagnoses and treatments.

Researchers at MIT recently developed micrometer-scale antennas that use light to monitor minute electrical signals in liquids. Known as Organic Electro-Scattering Antennas (OCEANs), the antennas provide a powerful new way to study cellular communication.

A graphical representation of OCEANs.

By eliminating the need for wires, OCEANs could overcome longstanding challenges in biosensing and open up possibilities for advances in biology, medicine, and technology.

How OCEANs Work

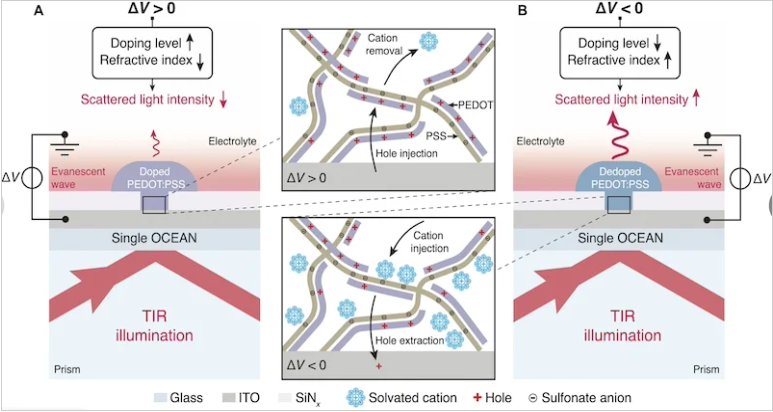

OCEANs are arrays of tiny antennas, each just one micrometer wide—one-hundredth the width of a human hair. Built on a glass substrate, they consist of layers of conductive and insulating materials carefully arranged to optimize performance.

When light shines on an antenna, the intensity of the scattered light changes based on the electrical signals in the surrounding liquid. This allows the antennas to act as independent sensors, capturing high-resolution data on electrical activity without requiring any physical connections.

Concept behind OCEANs.

This approach is a major departure from conventional systems. Traditional wired devices, commonly used to monitor electrical signals in cell cultures or liquids, face several constraints. Each wire represents a single recording site, and the number of sites is limited by the physical space available for connections. OCEANs sidestep this limitation entirely, enabling a dense array of sensors to gather far more data than previously possible.

Sensitive and Fast Micro-Antennas

OCEANs bring several advantages that set them apart from existing methods.

One is sensitivity; in simulated experiments, the antennas detected electrical signals as small as 2.5 millivolts—an impressive feat for devices operating in liquid environments. They’re also fast. OCEANs can respond to changing signals in just a few milliseconds, allowing them to record rapid electrical kinetics. This level of responsiveness is critical for studying dynamic processes like neural activity or the way cells communicate with each other. Durability is another key strength. The antennas can wirelessly and continuously record signals for over 10 hours, proving their robustness for extended experiments.

Perhaps most importantly, OCEANs are scalable. The efficient and adaptable fabrication process allows researchers to create chips containing millions of antennas. This scalability opens the door to studying large, complex systems, such as interconnected neural networks or massive cell cultures, at an unprecedented level of detail.

Promise in Cell Communication and Beyond

The MIT team anticipates OCEANs' utility in studying cell communication. Cells rely on electrical signals to coordinate activities, respond to environmental changes, and carry out complex processes. OCEANs can help researchers monitor these signals with far greater spatial and temporal resolution than current technologies allow.

This capability could also advance medical research. For instance, the researchers say OCEANs might help identify how abnormal electrical signaling contributes to diseases like arrhythmia or Alzheimer’s. Such insights could lead to better diagnostic tools and more effective treatments.

In drug development, OCEANs could play a role in evaluating the effects of new therapies on cellular behavior. OCEANs may also be integrated into nanophotonic devices for next-generation sensors and optical systems to influence fields like engineering and telecommunications.

In the future, the MIT research team plans to test OCEANs with real cell cultures. They’re also working on reshaping the antennas to penetrate cell membranes, which could enable even more precise measurements of intracellular electrical signals.